By: John Rubino

By: John Rubino

One of the jarring — and until recently underreported — aspects of those seemingly-positive recent US jobs reports is the increasing skew towards older workers. Most new jobs have gone to people who in better times would be leaving to live off their savings. Now they’re coming back, frequently taking jobs they wouldn’t consider if money wasn’t so tight.

And it’s apparently a lot worse for older women:

How Older Women Are Reshaping U.S. Job Market

(Wall Street Journal) – More female workers delay retirement, a shift that’s helping to transform America’s economy.Connie Blanchette, age 72, is a relative newcomer at the county social-services agency where she works part time, so her retirement plans differ from most longtime government workers. “I will work as long as I can,” she said.

Ms. Blanchette, who lost her job, home and savings after the financial crisis, is among a wave of older American women who are working or seeking work longer than any previous generation as they look ahead to more years of life than men their age and with less accumulated wealth.

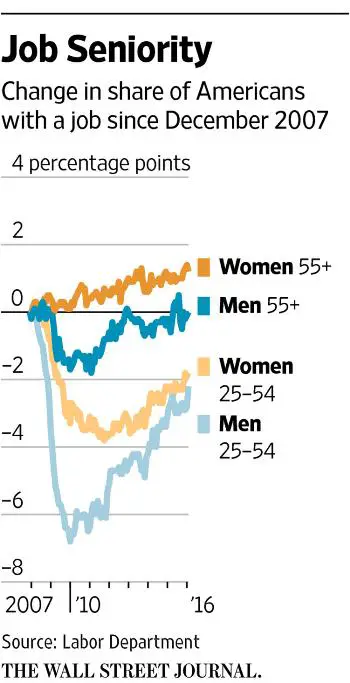

Since the start of the most recent recession in December 2007, the share of older working women has grown while the percentage of every other category of U.S. worker—by gender and age—has declined or is flat.

In 1992, one in 12 women worked past age 65. That number is now around one in seven. By 2024, it will grow to almost one in five, or about 6.3 million workers, according to Labor Department projections.

“It’s really one of the most stunning developments that we’ve seen in the labor market over the last 50 years,” said Richard Johnson, director of the Urban Institute’s program on retirement policy.

While many Americans continue working late in life because they find their jobs rewarding, others, including Ms. Blanchette, find themselves approaching old age with more debt, less savings and with fewer of them receiving pensions than workers of previous generations.

From the end of World War II to the 1980s, the share of older Americans in the workforce fell every year. That reversed by the mid-1990s, as companies shifted from traditional pension plans—which paid fixed benefits at specific retirement ages—to 401(k) savings plans, which transferred the responsibility of funding retirement to employees.

The past recession made things worse, forcing many workers out of jobs before they could afford to retire. While older workers were less likely to lose their jobs in the recession than younger workers, the older workers who did, particularly women, were hit hardest, according to researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

As older workers keep a tight grip on their jobs, the proportion of Americans ages 25 to 54 who are working or looking for work has slipped to the lowest level in three decades. Many of these younger Americans fell out of the labor force in the recession: Some retired or enrolled in school. Others weren’t able to work or had to care for relatives at home. Many gave up looking.

The behavior of older workers are pieces of a puzzle that policy makers are examining to answer questions about sluggish wage growth. Wages are determined largely by the amount of idle capacity—known as slack—in the economy. When there are many more people than available jobs—lots of slack—wages stagnate. When employers face a shortage of workers, wages rise.

The U.S. unemployment rate fell below 5% last month, a level not seen since early 2008. That drop, which happened faster than many economists had expected, should trigger employers to offer higher wages as they chase fewer potential hires. But the textbook case is muddled by the shifting demographics of the U.S. workforce.

Older men and women are leaving the workforce more slowly than in the past, suggesting a greater potential labor supply—and more slack—than an unemployment rate below 5% would typically imply. Such economic slack must be cinched—by finding jobs for discouraged younger workers, for example—before wages can rise more broadly.

Some thoughts

Defined-benefit pension plans are both an artifact and a victim of the credit bubble that began when the US left the gold standard in 1971. Freed from monetary restraints, government spending soared and — as a result — interest rates were kept artificially low, encouraging the private sector to over-borrow as well.

All this leverage created a false sense of prosperity that led businesses and governments to offer pension plans designed to buy labor peace in return for huge future payouts — premised on the expectation that investment returns would stay high forever.

But since returns were artificially inflated by easy money, the end of the latter made the former unsustainable. So pensions are being shut down and/or scaled back everywhere, kicking one leg out from under the concept of long, comfortable, broad-based retirement.

Add in continuously-falling interest rates (as governments try to keep the charade of solvency going long enough for current leaders to retire), globalization that shifts factory jobs overseas, and technology that is now automating virtually everything from warehouses to finance (see The Robots Are Coming For Wall Street) and the result is a society where only two groups can reasonably expect to retire: the already-rich and those with skills that haven’t yet been automated.

Meanwhile, seniors taking jobs on pretty much any terms are pushing down wages for younger people, making it harder for them to simultaneously pay off student loans and save — thus putting their retirement even further out of reach.

In rich countries, this is a return to the way things were for the first 10,000 years of human history, when the idea of an able-bodied non-aristocrat just sitting around and relaxing in old age was absurd to the point of being inconceivable. It’s also a transition to the way things have always been for the rest of today’s world.