By: Harold Jarche

This is a synopsis of my opening keynote for the workplace learning & VET stream at EduTECH15 in Brisbane today.

We cannot look at the 2020 workplace merely from the perspective of what will be different from today, as if these five years will pass in splendid isolation. How we think of work has changed over the millennia and one major factor has been our communications technologies. When communication changes, work does too, as well as our understanding of what is knowledge, and what it means to be knowledgeable.

When our various civilizations shifted from a predominantly oral society to the rule of the written word, we saw the rise of kingdoms and institutions. The age in which Socrates was able to guide discourse in the open agora was slowly replaced by structured academies, in the spirit of Plato. But Socrates felt that men who relied on written words would be a burden to their fellow men, as these artifacts would give them the ‘conceit of wisdom’. Despite Socrates’ reported concerns, the written word dominated for over 2,000 years.

When the written word was usurped by the printed page, the sharing of knowledge exploded. Bibles printed in the vernacular showed the common people that often their priests had hidden much of the text from them. This questioning helped to give impetus to the Protestant reformation and the age of enlightenment, which revived the classic Greek science and philosophy texts that could now be easily shared in print. The accessibility of books enabled more universities to be built, and printing helped to create better bookkeeping systems, so that global markets could flourish.

The printed word continued to dominate, even as it was initially obsolesced by the electric impulse, first with the telegraph (dashes & dots) in 1844, followed slowly by radio and television (electrical signals), and only recently gathering speed with the Internet and the Web (zeros & ones). The next five years will be an acceleration of a phenomenon that began in the mid-nineteenth century: the electrification of knowledge.

Each time that our mode of communication changed, so too did our dominant organizational structures. We went from Tribes, to Institutions, to Markets, and now to Networks. This is David Ronfeldt’s TIMN model, which aligns with historical changes in communication technologies.

In Tribes, power was often controlled through the bonds of kinship. People frequently did things for the betterment of their family. Members of a tribal group would cooperate with each other, as this was best for the longevity of the tribe. In institutions, power was controlled through the hierarchy, so individuals held their power by the virtue of their position. Work was done collaboratively, directed by those in control. As markets dominated, work continued to be collaborative but more competitive. The aim was to dominate the market. But as we move into a network society, for which we have no precedent, it appears that the cooperative behaviours of tribes may be the best way to work together, as our reputation in the network becomes visible to all.

In Tribes, power was often controlled through the bonds of kinship. People frequently did things for the betterment of their family. Members of a tribal group would cooperate with each other, as this was best for the longevity of the tribe. In institutions, power was controlled through the hierarchy, so individuals held their power by the virtue of their position. Work was done collaboratively, directed by those in control. As markets dominated, work continued to be collaborative but more competitive. The aim was to dominate the market. But as we move into a network society, for which we have no precedent, it appears that the cooperative behaviours of tribes may be the best way to work together, as our reputation in the network becomes visible to all.

Cooperation, giving freely with no expectation of direct reciprocity, makes sense in family groups, and is the optimal behaviour in knowledge networks as well. Cooperative behaviour enhances one’s reputation and creates more links in a network. Those with more connections can exert greater influence, but this is usually indirect.

The current speed of change from markets to networks is evident in the automation of human work. Automated tellers are an obvious example. Even higher level work is getting automated, such as legal discovery, once done by armies of lawyers and now replaced by software. Since the beginning of the century, routine work, both cognitive and manual, has decreased, while non-routine work has increased. This is a direct result of automation in all fields of work, whether it be self-serve kiosks, software replacing accountants, or driverless cars. As one recent article stated, “Self-Driving Trucks Are Going to Hit Us Like a Human-Driven Truck”. Automation is eating jobs.

Any work that is routine will be automated. Jobs that only do routine work will disappear. Valued work, enhanced by our increased connectivity, will be based more on creativity than intelligence. The future of human work will require tacit knowledge and informal learning, and will create intangible value that cannot easily be turned into commodities. The future of work will be complex and this will be even more obvious in the next five years, as robots and software keep doing more complicated work. Just as people had to become literate to work in the 20th century workplace, now they will have to be creative, empathetic, and human: doing what machines cannot do.

To deal with this work shift, people need to engage with professional communities in order to share tacit knowledge through conversations with trusted colleagues. Work silos are barriers to knowledge-sharing, as are education silos.

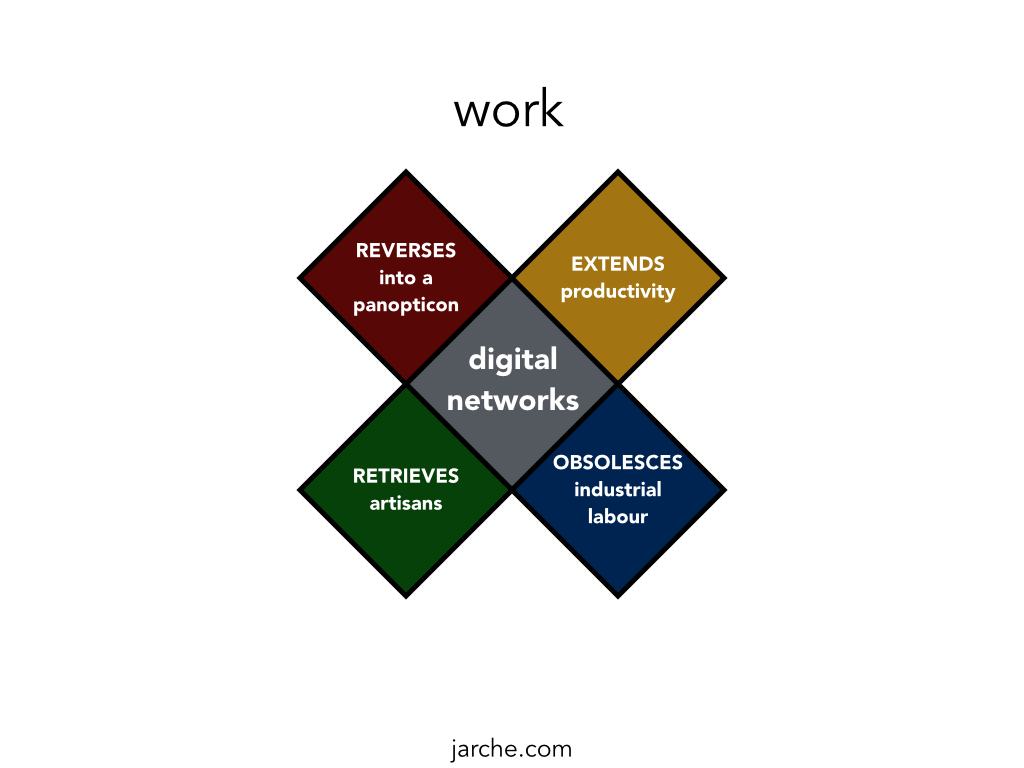

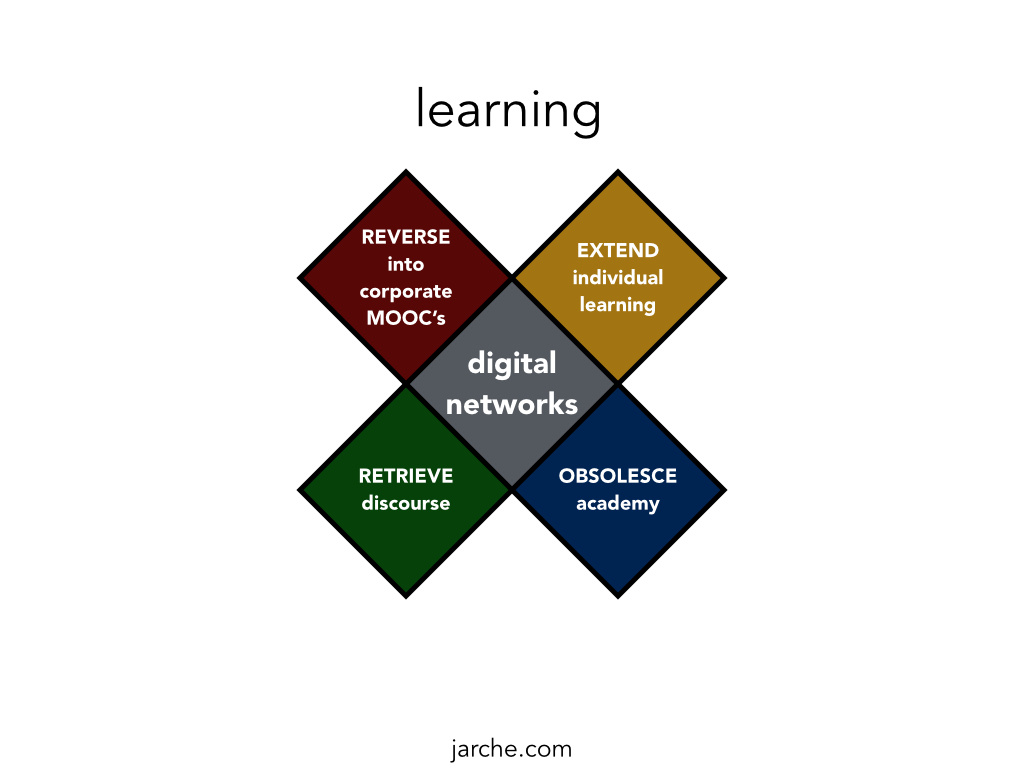

Marshall McLuhan gave us “the global village” as well as the aphorism that “the medium is message”. Even the typographical error in the book’s title, “The Medium is the Massage”, reinforced his point that communications media have strong influences on society. McLuhan’s Laws of Media can help us see what influence technology has on us. The media tetrad, explained by Derrick de Kerkchove, co-author of McLuhan for Managers, is that every technology has four effects.

1. extends a human property (the car extends the foot);

2. obsolesces the previous medium by turning it into a sport or a form of art (the automobile turns horses and carriages into sports);

3. retrieves a much older medium that was obsolesced before (the automobile brings back the shining armour of the knight);

4. flips or reverses its properties into the opposite effect when pushed to its limits (automobiles, when there are too many of them, create grid lock)

Let’s look at pervasive digital networks, currently known as “the cloud”. All of this open knowledge extends democratic and open structures, with growing experiments such as blockchain for finance or open source software. This shift to one big computer obsolesces the personal computer, with most computation now taking place beyond the individual’s control. As a result, off-grid computing and even the use of typewriters to avoid the Internet are now the realm of the rich and powerful. This pervasive digital network is retrieving the communal cooperation of the tribal era, with crowd-sourced fundraising and shared common goods, facilitated by trusted connections. However, the cloud can easily reverse into a panopticon of deception, as is already manifested through wide-ranging government surveillance and growing cyber crimes.

What can the tetrad tell us about learning? Networked learning extends individual control over personal and professional development, as articulated in personal knowledge mastery or personal learning networks. It obsolesces the hierarchy of the academy, opening education to more people, but makes private schooling an in-demand luxury. Social media retrieve the discourse of the age of Socrates, providing a public agora for all to engage. However, when pushed to its limits, networked learning may become nothing more than massively open online courses pushing a corporate agenda.

The retrieval of Socrates and the fuzziness of discourse reflects the complexity of the network era. Work is too complex for the structured academy. Training and education systems, run by a central authority (the academy) are effective when developing instruction to deal with complicated phenomena, where all the components are understandable and can be analyzed and mapped. Best practices and good practices can align easily with a curriculum. But in complex environments, emergent practices need to be developed while simultaneously engaging the problem. Social learning is the process by which groups of people cooperate to learn with and from each other. As discourse replaces the academy, social learning in knowledge networks replaces training and education.

The retrieval of Socrates and the fuzziness of discourse reflects the complexity of the network era. Work is too complex for the structured academy. Training and education systems, run by a central authority (the academy) are effective when developing instruction to deal with complicated phenomena, where all the components are understandable and can be analyzed and mapped. Best practices and good practices can align easily with a curriculum. But in complex environments, emergent practices need to be developed while simultaneously engaging the problem. Social learning is the process by which groups of people cooperate to learn with and from each other. As discourse replaces the academy, social learning in knowledge networks replaces training and education.

If you are involved in workplace learning or education, consider these changes in how we communicate, organize, and work.

- How important is developing new content, as opposed to helping make connections?

- How can we help people get better at creating new practices, and not just replicate old ones?

- How can our organizations promote better and deeper conversations?

- How can we help to build trust so that people freely share their knowledge?

We know that the machines will continue to improve. Barring the collapse of civilization, digital networks are here to stay. In the network era, work is learning and learning is the work. Our job, as learning professionals, is to make humanity the killer app for our organizations. While 2020 will not be that different from 2015, it will be further along the progression into the network era and a shifting world of work and learning, away from routine jobs and toward unique and creative work. This has to be supported through widespread opportunities for informal learning and ways to share tacit knowledge. This is the challenge for workplace learning as well as higher education.

http://jarche.com/2015/06/preparing-for-2020/?utm_content=bufferdd807&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer

http://jarche.com/2015/06/preparing-for-2020/?utm_content=bufferdd807&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer