LAS VEGAS—Long-term unemployment was a phrase you heard a lot about during the recession. Numerous studies showed that people who were out of work for long periods of time had a hard time finding a new job—and keeping it. And about one-third of those unemployed workers eventually gave up and stopped looking for work, studies suggested.

For all the recent good news about the booming job market and growing wages, there are still people out there desperately looking for work. Nearly 3 million of them—about one-third of all of the jobless—have been out of work for 27 weeks or longer, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In past recessions, a far smaller share of the jobless had been out of work for so long.

But states grappling with tight budgets have lost their sympathy for the long-term unemployed as the economy turns a corner. In the last two years, seven states have reduced benefits to 20 weeks or fewer—26 weeks of unemployment benefits used to be standard. The share of the unemployed receiving benefits now stands at 27 percent, according to a report from the National Employment Law Project, which is an all-time low.

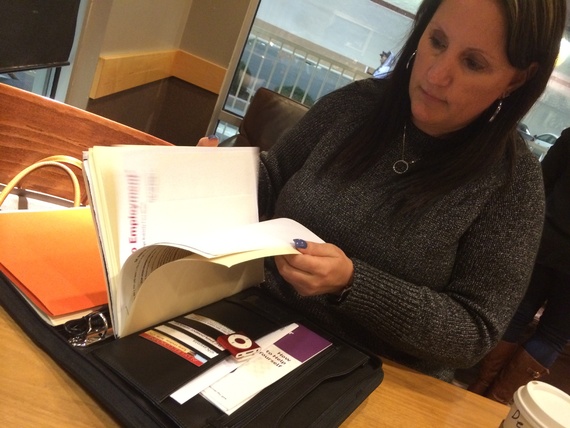

Until recently, De Ann Jensen was struggling to cope with these changes. The 47-year-old Las Vegas resident lost her job as a construction administrator in January of 2014, and had been looking for work ever since. When her benefits ran out in July, she couldn’t make her mortgage payments anymore, and was forced to sell her home in a short sale and move in with her parents.

She’d spend hours on the computer applying for jobs, but noticed after a few months that employers had stopped even inviting her in for interviews. It didn’t take long to become mired in depression, staying in bed and watching TV, wearing pajama bottoms for days on end.

“I would sleep all day long, and say, ‘Why should I look for a job? I’m just going to get the ‘Thanks but no thanks’ letter,” she told me.

But now, Jensen is working full time again, partly thanks to a program called Platform to Employment that was launched in Nevada last fall using federal funds. The program provides a selected group of long-term unemployed with an intensive five-week, job-readiness class, and then offers to cover up to two months of their salary for any employer willing to give them a trial. P2E was first launched with private funding in Connecticut in 2011 and has been piloted in 10 cities since then also using private funding.

Nevada is the first state to use federal funds to administer the program. Colorado and Indiana have also received the okay to use federal money, and in June, Connecticut’s legislature agreed to use $3.5 million in state funds to run the program for 500 residents.

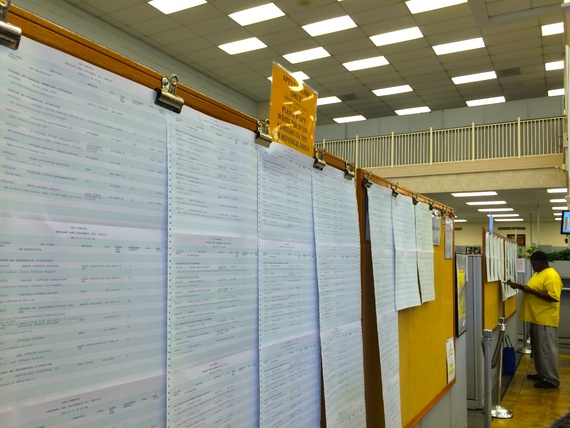

“I believe everyone would benefit from a program like this. Most employers are looking at being out of work for six months as too long,” said Patricia Nelson, a career counselor at a state-funded JobConnect center in Nevada. She recently helped a client who had been out of work for a long time enroll in Platform to Employment. He got a full-time job soon after completing the program. Nelson and I spoke in the crowded JobConnect office, where dozens of clients lined up looking at postings on job boards, waiting to use the computers and phones to apply for positions.

They included Lajuana Jones, 32, who moved to Las Vegas from Colorado in early September and has yet to find a job. She has a silky voice, perfect for her career in customer-support, but she can’t find work.

“It’s pretty bad here,” she told me.

The long-term unemployed might have a particular challenge in a market like Nevada, where unemployment is still relatively high at 6.8 percent, but tens of thousands of people arrive every year from more expensive states like California, or colder ones such as Colorado, creating more competition for work.

Many of the long-term unemployed would benefit from Platform to Employment, but so far, it’s been limited in Nevada to one class with only 24 people in Las Vegas and a class 0f 26 in Reno.

The program is expensive to administer—about $6,000 a person. But it gets results. On average, the program has placed 80 percent of its participants, and 90 percent of those people were kept by employers after their trial period. No other workforce-training program has success rates like that.

“We were allowing these folks to become more and more hopeless every day,” Joseph Carbone, who founded the program in Connecticut, told me. “There was something un-American about that.”

* * *

There are important economic reasons to help the long-term unemployed get back to work. After 15 months, the long-term unemployed were more than twice as likely to have withdrawn from the labor force than the short-term unemployed, one study showed. In January, 2.2 million people were “marginally attached” to the labor force, which meant they wanted work but had not searched in the past month. Many of the long-term unemployed apply for disability insurance once they run out of benefits, and once they get on the disability rolls, they’re unlikely to work again.

Long-term unemployment can also “have important spillover effects on the community as a whole,” according to a report by the Urban Institute, Consequences of Long-Term Unemployment. Long-term unemployment reduces investments in housing (people who don’t have jobs don’t buy houses), and also induces some people to participate in criminal behavior to earn money, the report indicates. One study showed that workers affected by plant closings have a 14 percentage point higher probability of being arrested, for example.

But few government programs are able to help the long-term unemployed get back to work, said Carl Van Horn, the director of the Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers.

In general, workforce programs are designed for people who haven’t been out of work for long. They provide a short burst of cash to tide people over until they can get back to work, or help young people get a degree so they can get a higher-paying job.

“Programs designed to help are really targeted at the short-term unemployed,” he said. “But that’s not the kind of economy that we experienced in the recession and its aftermath.”

Perhaps frustrated by the lack of programs available to them, many of the long-term unemployed don’t seek help when looking for a job at all. In a survey published in September, Van Horn and his colleagues found that only one in six unemployed workers visited a federally-funded, One-Stop Career Center, and only 10 percent of the long-term unemployed attended a job club or professional-networking meeting.

“If you’re not on unemployment insurance, the government has less interest in you,” he said. “These folks are left on their own, in a sense.”

Even though the economy is improving, the country’s programs to assist the unemployed need to be retooled, according to the National Employment Law Project, which this month published a report, The Job Ahead: Advancing Opportunity for Unemployed Workers. It recommends that lawmakers create wage-subsidy programs to help get the unemployed back to work, provide 26 weeks of benefits for jobless workers getting training, and promote work-sharing programs, which would reduce employees’ hours at a given company rather than having mass layoffs.

The basic structure of unemployment agencies should be retooled too, the report says. Many state agencies use technologies that are more than 25 years old, and have backed away from helping job seekers.

“With shrinking resources, many states have moved away from staff-assisted services towards self-service options,” the report says.

That means that some job seekers have done everything right, but haven’t been able to take that final step towards employment. They include Blaine Garner, who moved from Philadelphia to Las Vegas to expand a boxing-promotion business he started. Often, the long-term unemployed find that entrepreneurship can be a good way to get back into the workforce, but Garner has been bogged down by regulations and paperwork and is now looking to get a job in his old field of industrial maintenance.

He has an engineering degree and has applied for dozens of jobs, to no avail. When he moved to Nevada, his unemployment benefits were reduced, too. Now, he’s frustrated, and hasn’t gotten much help.

“If I’d have known what it would be like, I wouldn’t have moved here,” he said.

There are millions of qualified people like Garner looking for jobs, but as the economy has improved, policymakers have lost interest, said Carbone, the founder of Platform to Employment. In 2011, Carbone, the president of the WorkPlace, a workforce-development board in Connecticut, decided he didn’t want to just take a pass on the problem of long-term unemployment. He started going to foundations and wealthy donors, asking them to give money for a program percolating in his head. It would help the long-term unemployed get their confidence back, and also offer a financial incentive for employers thinking about hiring these workers.

He raised $600,000 and launched a pilot program, which accepted five classes of 25 students out of 400 total applicants. The first class set the precedent for how the other efforts have panned out: Participants attended a five-week class during which they learned how to interview and how to improve their resumes. They were required to meet at least once with a mental-health counselor and received counseling about improving their self confidence. At the end of the program, they applied for jobs, and the P2E program paid 100 percent of their first month’s salary, and 50 percent of the second month’s. The employer could drop out of the program at any time. Few did.

“We truly made a deal that was hard to refuse,” Carbone said.

* * *

When the phone rings at the Milan Institute, a career college in Las Vegas, it is answered by a cheerful woman named Cymphonie Redic. She transfers calls while processing student payments and directing prospective students to fill out forms, all with a bubbly, happy manner.

Until a few months ago, Redic, 31, was struggling to find work and support her 3-year-old daughter. Out of work since November 2013, she was relying on benefits such as welfare and food stamps, getting more depressed every day.

Then she read a news story about Platform to Employment launching in Nevada. She applied right away, and convinced the director that she’d thrive in the program. She enrolled, spiffed up her resume, and a few weeks in she got an interview with the Milan Institute after a career coach from P2E recommended her to Christopher Moderson, the school’s director.

“We interviewed Cymphonie and said, ‘Hands down, we’re done, she’s got every characteristic we’ve been looking for,’” Moderson told me. “From the moment she set foot in the door, you could tell that she was serious about wanting to work, and wanting to do a great job for whomever she worked for,” he said.

Getting an outside organization to pay her salary for the first month didn’t hurt, he said. But Redic did such an outstanding job that she was soon promoted to help manage inventory, too. Moderson said he could see her eventually rising in the organization to help direct programming.

Indeed, the long-term unemployed can often be more motivated to prove themselves than others who have been out of work for only a short time. That’s true even if they’ve accepted a job for less money than they were making before the recession, which most are forced to do. They know, by now, that they can’t hold out for something that pays more.

“After a whole year of getting up and not being able to go anywhere, I will skip to work now,” Redic told me. “I wake up so happy every day.”

That’s something Moderson himself knew. He said he didn’t have bias about Redic’s long spell of unemployment because he, too, had once been out of work for more than a year.

It was an empathy for the long-term unemployed that motivated Joseph Carbone to found the program. He had once been unemployed for nine months, and knew how isolating it could be. So he started holding roundtables with people who had exhausted their benefits in Connecticut, and found that many were facing foreclosures, divorces, and nervous breakdowns.

“What happens to people is that they become hopeless, they just kind of drop into the abyss,” he told me.

The program helped many participants get into a daily routine and talk to other people who were experiencing the same isolation and frustration they were.

Because they were required to see a therapist at least once, and had counselors visit the classroom, participants began to talk about the feelings of shame and frustration that they’d battled.

“They’re going to talk about their experience, they’re going to cry, they’re going to get it out of their system,” Carbone said. “It’s incredibly important to get it out of their system.”

Once they spoke candidly about their unemployment experiences, participants gained their confidence back, he said.

If nothing else, that part of the program could be replicable at a lower cost in cities and states across the country. After all, giving the long-term unemployed a new community and peers to help boost their confidence might mean they don’t need as much hand-holding from paid professionals.

De Ann Jensen, the recently reemployed Las Vegas worker, says the catharsis was the most important part of the program for her. She was skeptical about some other parts of the curriculum—a counselor who came in and had participants draw with crayons, for one. And she isn’t sure that her new resume is any better than her old one.

During the program, an employer saw her old resume and called her about a job. She was hired after an interview, and the employer decided not to use the salary Platform To Employment had offered to pay. Sometimes, Jensen wonders whether she would have been hired even if she hadn’t gone through Platform to Employment. But it’s possible she wouldn’t have been confident enough to even apply without the program.

“We bonded like a family—and they were always there to support you,” she said about the class. “If you’re having a hard day, if you’re having a bad day, there was somebody to talk to. We all still talk to each other.”

One day during the program, a speaker came in and talked to the group about shame. It hit everyone hard, Jensen said. So many participants had been ashamed of being unemployed, and had begun to feel hopeless. When they talked about these experiences, sometimes with tears, Jensen said, she realized she had to take control of her life.

She still has a while to go before things are back to normal—she makes $16 an hour, that’s less than she made in her old job. And she still lives with her parents and three cats, since she’s behind on her bills and can’t yet afford her own apartment. But she’s confident she’s on the way back up.

“There would be days I wouldn’t get dressed, I wouldn’t open the blinds, I’d just sit there and watch TV,” she said. “Now I have a purpose. It’s so much better.”